|

|

|

.

Features

Update 2020/8/17

Mining

COULD NEW FRACK PROJECT TURN MANITOBA’S BROKENHEAD RIVER INTO A TOXIC NIGHTMARE WHILE COMPROMISING THE WINNIPEG FORMATION AQUIFER?

By Suzanne Forcese

The Brokenhead River begins its 200 km journey from a wetland area of Sandilands Provincial Forest located in southeastern Manitoba, flowing through the Brokenhead First Nations land to its final destination, draining into Lake Winnipeg.

This same Manitoba geography also sits atop the Winnipeg Formation.

The Winnipeg Formation is the basal sedimentary unit throughout much of southern and central Manitoba, where it forms a regional aquifer over most of its extent. This aquifer is an important source of water in southeastern Manitoba and in Manitoba’s Interlake, but in most other areas, groundwater within the aquifer is saline.

“The flow system in parts of the area is not in a state of equilibrium and saline waters will encroach on areas currently occupied by freshwater in some areas...groundwater withdrawals will likely hasten these processes.”(Grant A.G.Ferguson, et al, Hydrology Journal, 2007)

Concerned citizens in Manitoba already fear for the Winnipeg Formation Aquifer’s capacity to provide potable water because of an Environmental Act Proposal. Adding to their dread, the entire watershed may now be facing the peril of becoming a toxic dumping ground.

A proposed frack sand project near Vivian Manitoba, initiated by Alberta based CanWhite Sands Corporation (CWS) is catalyzing their alarm.

Long-time Vivian resident, Tanzi Bell, told us, “The effects of CWS plans are of such magnitude and will generate a number of environmental, socio economic and health issues that we are asking that this exceptional project warrants being heard in whole, that the Clean Environment Commission conduct a public hearing and that intervenor funding be made available to ensure that an independent, thorough and in-depth analysis is awarded a project of this scale.”

WATERTODAY contacted What The Frack Manitoba, (WTFM) a not-for-profit organization whose mission is to provide timely and critical information on fracking issues of concern to all Manitobans. WTFM has stepped in to help citizens voice their concerns.

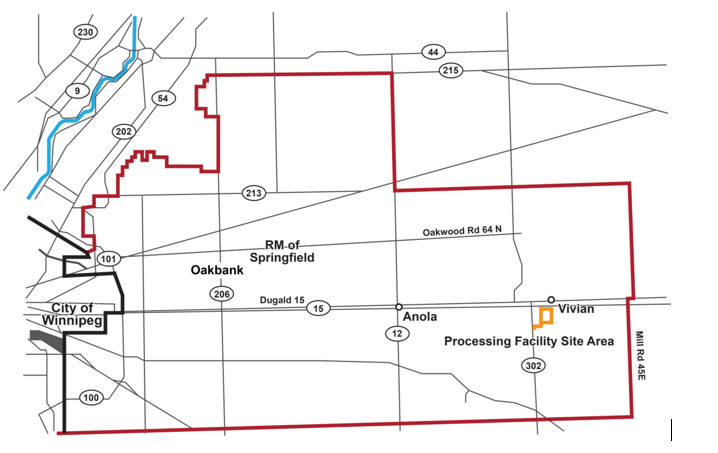

On July 16, 2020, CWS filed an Environmental Act Proposal (Manitoba Public Registry File #6057.00) with the Government of Manitoba for approval to construct a silica sand processing facility near Vivian in Southeastern Manitoba.

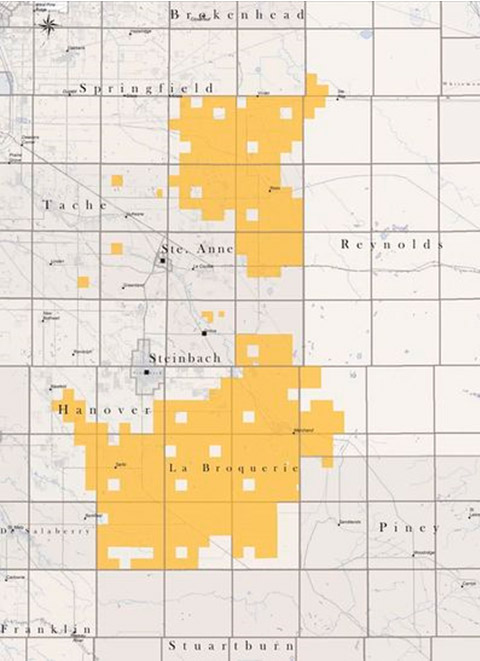

CWS has secured a total of 390 mining claims which covers 85,000 hectares of land.

Once the proposed silica processing facility receives Manitoba Environmental approval under the Manitoba Environment Act for its proposed silica processing facility, CWS intends to submit a second and separate EAP for environmental approval for its proposed silica sand mine and the mining method to extract silica sand.

“The splitting of a single proposed development project into two separate projects makes approval under the Manitoba Environment Act of the silica mine and the mining methods to extract the silica sand a forgone conclusion,” Don Sullivan, spokesperson for What The Frack Manitoba told WaterToday.

The proposed Vivian Sand Facility Project is within the RM of Springfield, selected for its proximity to existing CN Rail Infrastructure

According to the CanWhite Sands website: “CanWhite’s raw silica exceeds 99.85% purity prior to processing and is an irreplaceable ingredient in developing fibre optics, computer chips, integrated circuits, silica metals, photovoltaic cells glassware for synthetic and analytical chemistry, telecommunications, precision casting, medical equipment and desiccants.”

However, according to a video presentation made by Feisal Somji, President and CEO to a group of investors in Florida, November 2019, Somji states:

“We are a large Tier 1 sand resource in the frack sand business. The oil and gas industry is where the majority of our sand will be used in the fracking process….We really only have one competitor, Wisconsin Sands.”

Somji adds that most of the board members of CWS are in the oil and gas sector.

Somji’s pitch to the Florida investors highlights the advantages of the Manitoba location that will make CanWhite stand head and shoulders above Wisconsin Sands. Namely, they will offer a less costly product for the same quality Tier 1 white sand for the oil and gas industry in the Canadian Basin and Bakkan in North Dakota.

The Canadian Dollar, a unit train accessible facility, and cheaper electricity will allow CWS an advantage to the same markets Wisconsin Sands serves, according to Somji.

Somji also claims that “by using an innovative borehole mining technique we reduce our environmental footprint.”

“Once silica sand is sucked up to the surface through hundreds of boreholes per year,” WTFM’s Sullivan says, “and after going through the wet plant, the stock-piled silica sand will contain a percentage of water.”

Sullivan tells us, “Based on the information contained in CWS EAP, the company indicates that 15% of what they will extract from 200 feet below the surface in the Winnipeg Formation Aquifer using solutions mining method will be solids (silica sand and shale).

“The remaining 85% will be water...although not explicitly mentioned in CWS EAP.”

The proposed Processing Facility “The Vivian Sand Project”. CEO Feisal Somji states

“No water is needed for the Wet Plant as it will all be recycled in a loop system.”

No information is given by CWS as to the yearly discharge of 6.5 million

cubic metres of water brought to the surface in the extraction process.

After several attempts to speak with Feisal Somji, WT received an email response.

“It is a very hectic time and we are working tirelessly to ensure all the correct testing and science is occurring to give comfort to those with concerns relating to our operation,” Somji replied, explaining that “our facility will primarily be drying and screening the sand which is delivered to the facility by a closed loop system utilizing recycled water.”

And just how much water?

“The facility will use 200-300 gallons of water per day,” Somji writes.

But there is another water issue that deals with the extraction process that Somji did not address.

CWS expects to produce 1.36 million tonnes of market-ready silica sand per year.

“After doing some basic math based on 15% of what is being extract will be solids, we know that in order to produce 1.36 million tonnes of silica sand per year, CWS will also need to extract 7.7 million cubic metres of water on an annual basis,” Sullivan contradicts.

“This 7.7 million cubic metre withdrawal on a yearly basis will also pose a serious problem for those in southeastern Manitoba who rely on this aquifer annually and will certainly inhibit the ability of this aquifer to recharge itself,” Sullivan continues.

Putting this into perspective, the average Canadian uses 329 litres of water a day. Thus 7.7 million cubic meters of potable water per year would serve a population of 64,121.

“It is anticipated roughly 6.5 million cubic meters or more, of the 7.7 million cubic meters of water extracted yearly will need to be discharged,” Sullivan continues.

This discharge of 6.5 million cubic meters of water annually is anticipated to be released into the Brokenhead River which drains directly into Lake Winnipeg and will contain high levels of heavy metals, chromium, arsenic, neurotoxins and will be acidic, as pyrite in the shale withdrawn with the sand and the sand itself will cause acid drainage and mobilization of heavy metals. – Don Sullivan, What The Frack Manitoba

In the CWS EAP for its proposed silica sand processing facility there is no indication where this large volume of discharged toxic water will go annually.

Since the fish bearing Brokenhead River runs through Brokenhead First Nation, it is running through Federal lands.

“To my knowledge,” Sullivan adds, Brokenhead First Nations has not been consulted by the Province prior to CWS EAP submission with respect to possible adverse impacts to Brokenhead FN Section 35 Rights.”

To release deleterious substances into the Brokenhead River would be a clear violation of Section 36(3) of the Federal Fisheries Act.

As the questions and concerns continue to come to the fore, What The Frack Manitoba Science Researcher, Dennis LeNeveu, brings another piece of unease to the conversation.

“In 2018 and early 2019, CanWhite brought up piles of the sand from 200 feet below the surface near Vivian by exploration solution mining,” WT learned from LeNeveu.

“The piles were left exposed on the surface. Concerned citizens gathered samples and had the sand tested by an independent certified lab.”

“Even though the sand had been leaching from exposure to air and rainfall for about a year the test revealed the sand still contained .47% iron; 0.9 ppm arsenic; 10 ppm barium; 5 ppm chromium and other heavy metals.” – Dennis LeNeveu, WTFM Science Researcher

According to LeNeveu, knowing the sand slurry will be 85% water, allows for an estimated pH level of 2.44.

“This acid will leach the heavy metals out of the sand,” LeNeveu adds.

Also large amounts of shale fragments are brought up with the sand. “The shale fragments were clearly visible in the sand brought to the surface in exploratory drilling.”

Shale is known to contain arsenic and pyrite which will produce more acid and mobilize more heavy metals.

In the CanWhite process proposed for the Vivian Project, after most of the sand is screened out in the wash plan, the excess water is routed to an outdoor clarifier tank where polyacrylamide flocculant is added to settle out the remaining clay silt and fine sand.

“Acid, sunlight and iron in the water is known to break down polyacrylamide into acrylamide, a neurotoxin carcinogen that can cause birth defects.” (Polyacrylamide Degradation And Its Implications in Environmental Systems, Boya Xiong et al, Sept 2018)

Should the Brokenhead River become a toxic dumping ground, What The Frack Manitoba’s Don Sullivan and Dennis LeNeveu have provided us with a clear picture of what this may look like.

On August 3, 2020, Sullivan and LeNeveu travelled to the south side of Black Island, immediately across from Hollow Water First Nation on the main land where a silica sand mine started up in 1929, changed ownership a number of times and eventually all operations there ceased in the late 1980’s.

Is this to be the fate of the Brokenhead River as it journeys toward Lake Winnipeg?

“At the abandoned quarry, purple staining can be seen coming from the water running through the shale layer. This is what primarily forms the blood red water,” LeNeveu says.

Should this be the Brokenhead River’s fate, some of the blood red toxic brew would infiltrate the carbonate aquifer. The majority would flow to Lake Winnipeg entering the biosphere and food chain.

CWS CEO Feisal Somji wraps up his email to WT:

“We are working hard to ensure all concerns are addressed with actual data and science to provide comfort to those with concerns. It’s unfortunate but there has been a lot of misinformation in relation to our project. We are hopeful that continued open communication and research will provide a more solid foundation for all.

“Our intention is to be in Manitoba for years to come and sharing information and being good neighbours is essential as we move forward.”

Back to that corporate video presentation to potential investors, Somji states:

“The business intent here is to build and sell. Wisconsin can come and take us. We want to prove to them that they should. And that’s the end goal for us.”

Questions continue to surface.

suzanne.f@watertoday.ca

|

|

|

Have a question? Give us a call 613-501-0175

All rights reserved 2024 - WATERTODAY - This material may not be reproduced in whole or in part and may not be distributed,

publicly performed, proxy cached or otherwise used, except with express permission.

|

|